Christmas 2015. Presents piling up under people’s desks at work after lunch-time shopping. No doubt some won’t quite hit the mark. But it’s the thought that counts.

When government spending doesn’t hit the mark it’s different. If I said to a bunch of neighbours over Christmas beers in my park, ‘Government wastes money’, most of them would agree. There’s a few things to talk about locally. In 2015 our municipal rates subsidised the mayor’s university degree to the tune of $16K. He should have stepped down in my neighbour’s view. And then not everyone thought it was a great idea to put in pop-up trees on High Street to test out a new urban landscape. ‘Waste of money! And someone’s going to have an accident. Probably cost a fortune!’

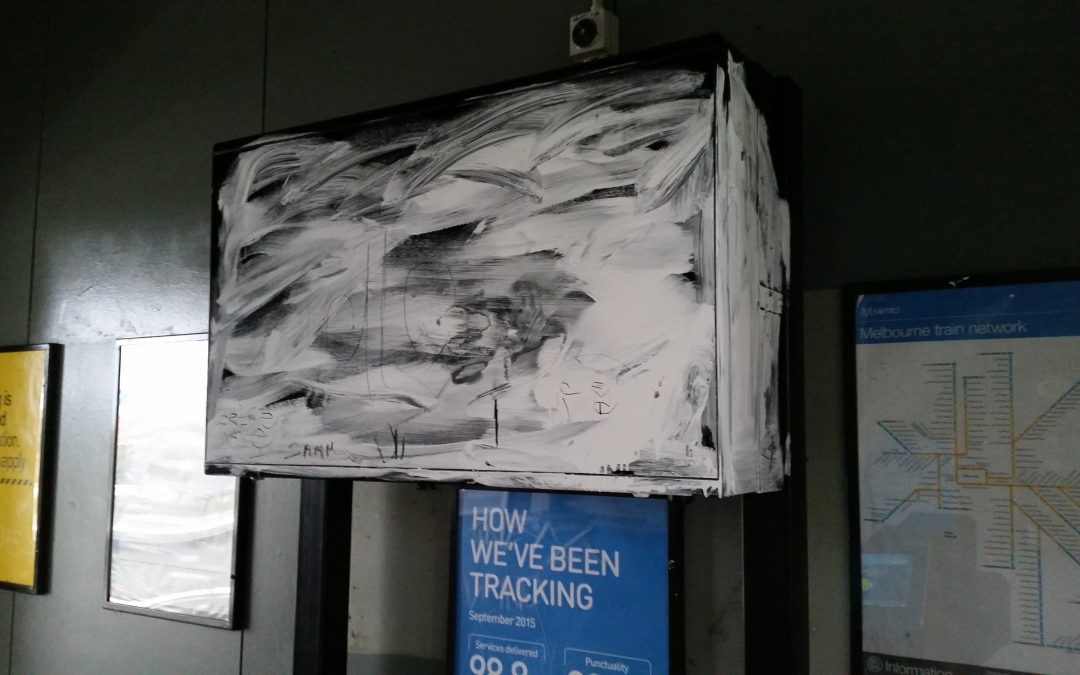

Then there’s the quirkier example from the railway station. When MetroTrains or Public Transport Victoria installed a large monitor in the entrance way, anyone could have told them it’d be graffited in five minutes.

Problems, solutions & waste

People perceive waste when they can’t see the relationship between the problem and the solution. In fact we see MetroTrains creating a new problem.

They had clean it up, then find something to stick over the broken glass, and finally turn it to face the wall and bolt in the expensive electronics.

And we never understood what they perceived as the problem in the first place. Was it a safety issue that a large black monitor would play a role in resolving? Was it a revenue problem that could be solved by playing advertising in our station entrance way? We just laugh and our cynicism compounds our sense that money is wasted for no good reason.

Community engagement

I want government to spend money well. Especially under constraints. In the example of the train station monitor, a five minute survey of people on the platform would have helped. However, in situations like local government rate capping, conventional community engagement may not be the answer.

Why not? Community engagement enables fantastic solutions to all sorts of local problems and situations, such as improving a playground or choosing trees for a local streetscape. But it’s less likely to work when a council is seeking guidance on rate contributions and spending at a municipal level.

Do we really want our councils to examine options that affect everyone with a small sample of self-selecting commentators? People who have come along to a workshop or responded to a survey because they feel strongly about expressing their view? No, there is already an issue. Council ‘experts’ meet ‘community experts’. ‘We know’ meets ‘we know better’. You asked us – now we’re telling you.

It doesn’t matter that Option 3 highlights that reductions in spending will result in hardship or adversity. It takes more information and more substantial discussion, framed in terms of a shared problem, to come to informed recommendations on public issues.

Thanks for the prezzie!

This group of people is having fun on new exercise equipment in their park. A prezzie from their fellow citizens, the Darebin Participatory Budgeting Jury, who decided in 2014 that it’d be good to spend part of a $2mil infrastructure budget on it.

The estimated cost was $300K. The jury’s rationale: 1. that research and evaluations show that people of all ages will benefit from use of public exercise equipment if it is easily available. 2. meets council goal of Healthy & Connected communities. Looks like they were proved right.

Here, a council stepped to the community’s side by inviting a randomly stratified group of citizens to spend four Saturdays at council learning about a problem and getting advice from chosen experts. The jury came to understand the council’s problem. If you only have $2 million to spend, it has to be allocated fairly, to benefit as many people as possible. They jury set about joint problem solving with the council.

It’s the thought that counts. That together government and citizens can ‘get to yes’ and become partners that make a difference.