How many times have you heard this old maxim? They don’t know what local government does. A maxim does express a general truth, but the good news is you can disrupt the general truth from time to time, to make the most of great opportunities. Disruptive innovation is a buzzword in business and entrepreneurship, but what does it actually do?

Disruptive innovation:

- Changes expectations of those who use your service

- Changes expectations in the broader sector

- Changes the paradigm of how you get things done

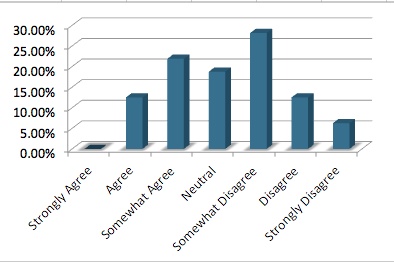

It takes commitment to work towards change like this, and really isn’t for those who only want business as usual (see Disruption, Good or Bad for Entrepreneurs). Disruption changes what people know about your service, local government. The graph below shows how jurors in a participatory budgeting jury at City of Darebin of Council self-rated their understanding of strategies and policies at the start of the process.

“I have a really good understanding of Council strategies and policies”. Darebin jurors’ self-rating at the start of the jury.

By the end of the Darebin jury, the majority of jurors self-rated ‘strongly agree’ or ‘agree’! They understood Council strategies and policies really well. I believe that participatory budgeting is a commitment to bring about changes like this.

In a recent article in Australian Policy Online I wrote:

“From their previous experience with community engagement, councillors and council staff are all too familiar with citizens taking up roles that impede problem solving. Deliberative methodologies present participants and staff with a threat-free path, in which effective task and affect type roles come to the fore in all contributors in the jury experience, in a context of learning, explanation and collaboration. In the early stages, it is common to see the roles of authoritative information giver and acquiescent information seeker to the fore, as was apparent in the first meeting of the City of Melbourne People’s Panel where jurors met Councillors and executive staff at table groups to learn about the main areas of budget allocation. However, by a later session, panel members’ information seeking roles were amplified by many other roles. Some were good reality testers, others informed critics. Group members with an eye on the time took the chance to provide summaries, and move the action on. Where Council players in the early appeared to identify as leaders and experts, unlikely to pause unless an insistent juror sought information on their own terms, they now displayed a different style of leadership, with a coordination focus, acting as communication helpers doing their best to field questions from each member of the table group. By now all contributors took a productive stance in building trust as they probed the terrain of budgets, services and infrastructure.

At Darebin there was strong evidence throughout the jury that members were in an unusual position to relate to council in productive roles: they became the initiators, for example by putting forward criteria for decision-making and initiating discussions with expert witnesses; they became critical analysts, approaching the selection of expert witnesses from the perspective of expertise available beyond council and undertaking critical examination of council strategies. They adopted the role of rational advocates, adopting evidence presented to them to inform the selection of decision-making criteria. Encouragers assisted older and younger members. A strong process observer called for clarification of process to ensure complete transparency in decision-making. Technicians took on reporting for the final presentation.” Read more.